Can Public Speaking Training Improve Your Mental Health?

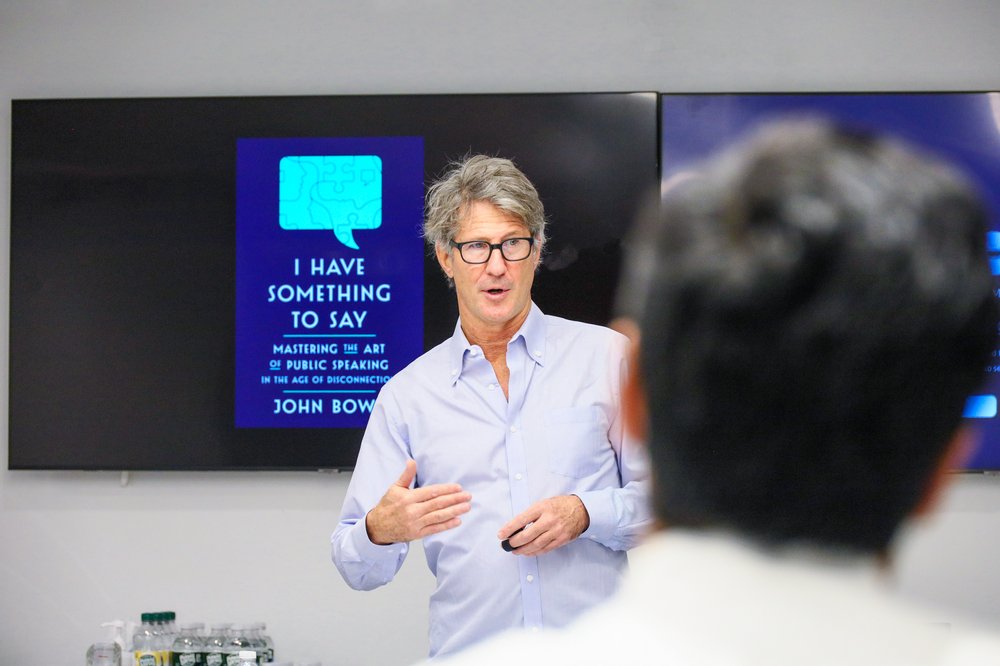

John Bowe is not your typical public speaking coach. He doesn’t always have a gleaming smile on his face, and it doesn’t always look like he is performing for you. Instead, you might picture him as an introverted writer, one who is deeply involved with words.

That is no accident. Before starting off as a public speaking and presentation expert, Bowe worked as an investigative reporter for The New York Times Magazine and The New Yorker. He’s also published four acclaimed books, including oral histories and a detailed account of modern slavery in the United States.”

His latest book, I Have Something to Say: Mastering the Art of Public Speaking in an Age of Disconnection, is an exploration of Aristotle’s rhetoric and the concept of speech training from ancient times to the present.

“A lot of people associate public speaking training with Dale Carnegie,” Bowe says. “It seemed cheap, uninteresting and inauthentic. I thought it was for uncool people, and that despite being bad at it myself, I was really cool.” So he devised a method to deliver speech training in another format, one aimed at a more reflective audience interested more in the content of the speech than the speaker’s presence, like himself.

The whole thing emerged from his own experience. As a journalist, Bowe presented his books on high-caliber shows like The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, but he felt he couldn’t properly articulate his thoughts. “I was resenting the world for not magically understanding me or resenting myself for being too inarticulate,” he says. He wanted to change the world with his books, but hated the public speaking part, constantly blaming himself for missed opportunities.

The words of change

“Ever since I was 8 years old,” Bowe recalls, “I wanted to make the world a better place with words. How did that come into my head? No idea. I think it’s just because my parents were fighting and I was desperate to find something that would make things safer.” For a couple years, he traveled around the world and went to film school before becoming a journalist. That led to years of interviewing regular people and telling their stories — oral histories, as Bowe likes to call them. “[It’s] that pornographic pleasure of a good documentary where you are psychologically and logistically sort of paratrooping into foreign territory and you find out what it’s like for a Christian lesbian baker in California or a fisherman in Alaska.”

While working on his book US: Americans Talk About Love back in 2010, Bowe interviewed his step-cousin in Iowa, an “amiable recluse” who had never had a girlfriend, lived in his parents’ basement, and only went out to go to church. That is, before he surprised his family by getting married at almost 60 years old. “How did you muster up the courage to ask someone to marry you?” Bowe asked him, assuming the response would include therapy, psychiatry, or meds — common tools for improving mental health.

“I joined the Toastmasters Club,” he answered. “Someone at church recommended it.” Bowe was floored — he later immersed himself in researching the influence of speech training.

Toastmasters International is the largest nonprofit platform that delivers public speaking training through almost 20,000 clubs around the world. Its founder, Ralph C. Smedley, was inspired by the ancient Greeks and Romans and started his first Toastmasters club in 1905. “It’s fascinating how the Greeks invented this stuff just five seconds after they invented democracy,” Bowe says. “Because the moment you have democracy, you have endless arguing and misinformation, you need to teach people how to grapple with that.” Smedley’s theory, in simple terms, is that a person should address a group just as he or she would address a single person.

The art of rhetoric in the ancient world

Putting yourself in your listener’s place is a recurring theme in the foremost book on public speaking, Aristotle’s Art of Rhetoric. That’s also the cornerstone of Bowe’s teachings. “You could meditate for a year on that, and just continue getting insight from it,” he says. “Eventually it affects your perception of yourself and your mental health in a positive way. You are going to start feeling more confident about it because you get prepared and think about what your audience needs.”

In his recent piece for The New York Times, Bowe argues that learning the art of rhetoric can help people connect and understand each other. In 2018, while working on I Have Something to Say, Bowe started sharing this concept with friends. As interest grew, he was charging $75 an hour for public speaking consultations. In a short time, his rates went up to $600 an hour.

from https://www.johnfbowe.com/

Talk therapy in action

When it comes to the mental health benefits of speech training, Bowe provides an example of a man who was trying to compensate by speaking too much. His boss refused to promote him because the guy was so verbose. Earlier in life, Bowe experienced something similar. “I was often trying to show how original I was, the most creative guy with all this traveling or drugs, playing creative instruments and working in film,” he says. “If you’re thinking about your audience, most likely they’re not there for that.” He said that three hours of speech training refocused the attention of that man on the needs of the audience, and that helped him curb the impulse to show off he says. Eventually, he admitted becoming more confident in himself.

For Bowe, the upside of learning public speaking is to be understood, which he’d been struggling to achieve for a long while. “I used to think the world was so dumb. No one’s ever going to understand anything. I realized it’s on me to be clearer and to be articulate and make myself understood.” Once he got over the notion that the world is obligated to understand him, he says, he felt less lonely.

As an investigative journalist, Bowe has reported on modern slavery and social issues, but he believes that an education in public speaking can do even more for the world. His idea is to restore the teaching of public speaking in schools, which can help students articulate viewpoints and engage in healthy debates, leading to better thinking and conversations.

“My childish mission to make the world a better place through words just nails that, and accomplishes that much more powerfully than what I did before,” he says.

| Prepared for Vivid Minds by | ||

|

|