How Fire Healed My Childhood Trauma and Led to a Radical Life Change

Stacy Selby

I threw up on fires.

That sentence sounds like gibberish. What I mean is, I was a firefighter and a bulimic, and sometimes, when working sixteen-hour shifts in the woods on elite firefighting crews, I threw up on purpose, worried a Snickers bar would make me fat. My bulimia started when I was eleven. When I was twelve, I smoked pot for the first time. At thirteen I snorted my first line of speed. By sixteen I’d done more drugs than most people will ever do in a lifetime. At nineteen, I became a wildland firefighter, and it saved my life.

Drugs, drinking, and parties

Aged 19, I dropped out of community college. It wasn’t that I didn’t like it: in my English classes I savoured Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, drama class made me dream of becoming an actor. But then my grandmother died of emphysema [severe lung disease].

I lived with my grandparents for two years when I was a child. My mom had dropped me off at their house and essentially vanished. Grandma and Grandpa weren’t particularly nurturing; Grandma worked as a night nurse and despite her regular trips to AA meetings nursed secret alcoholism, and Grandpa was a former Marine with PTSD. They knew me, though, better than anyone else. They loved me unconditionally, and I knew it. When Grandma died I felt like one of the only people I loved and trusted — was gone.

I dealt with it though drugs, drinking, and sex.

I stopped attending college. A friend from my English class was a drug dealer, and we became close. I washed his dishes for cocaine. I laughed hysterically while snorting ketamine in his bedroom.

When he was busy I hung out with other friends who drank with me, or did GHB and walked long loops through Eugene, Oregon, where I lived, looking for random parties.

One of my friends, watching me spiral, suggested I try wildland firefighting. It will take your mind off everything, she said. I wasn’t athletic, but I figured I could try. Besides, I needed money.

First encounter with fire

The classroom was in a little trailer off a side road, surrounded by a chain-link fence. I applied to work for a contract crew, which sold its crews to the government when they’d depleted their resources. After a week and a half in the classroom, we took the pack test (walking 3 miles in 45 minutes with a 45 lb. pack) and I miraculously passed.

On our first field day, I was second-to-last on the hike out. The guys I was with said they thought I wouldn’t come back the next day, but I did. Something about being out there in the burning woods, walking for hours and hours — something about it felt good.

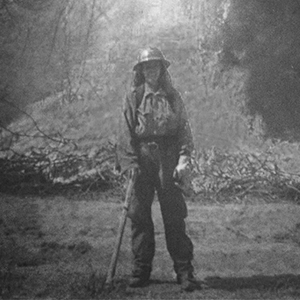

Two years later I took a job on an elite firefighting crew out of California. I was the only person who wasn’t a man. Back then I called myself a girl, though I’d never felt quite right saying “girl” or “woman” because I didn’t feel at home in that gender, but I had no understanding of any alternative (I am nonbinary and no longer identify as a woman).

Despite all the sexism and harassment I dealt with, the work grounded me. When I was out there, working long days, swinging my tool or running a chainsaw, I wasn’t drinking. I wasn’t using drugs. My head was clear.

But whenever we landed back in town after two or three weeks on an assignment we rallied straight to the bar. I often spent my days off drunk. I didn’t miss booze when I was working, but something about being out in the real world was too much for me.

Trauma and healing

I had trauma, but I didn’t really know the word back then. Childhood trauma from my mom’s abuse and neglect, teenage trauma from having run away several times, from having been homeless and having experienced sexual assault more than once.

The life I’d experienced up until firefighting had convinced me that I was inherently bad: a high-school dropout whose parents had both failed to graduate from middle-school, born into a religion some (rightfully) call a cult.

Shortly after my birth my mother left my father (and Scientology) in Southern California, and he was mostly absent throughout my childhood. In our household, with my father gone and my mom struggling with alcoholism and her mental health, college wasn’t something we talked about. We moved so often that I eventually stopped doing my homework, knowing it didn’t matter. Who I was didn’t matter. Nothing mattered, because we never stayed anywhere for long.

My last year of fire was in Alaska, in 2009. I was twenty-nine. I’d spent the previous winter in Seattle, trying to care for my mom, who was newly divorced from her second husband and spiraling into a deep depression and alcoholism.

One evening she shot herself.

I held a small memorial with the help of two of my mother’s close friends. She didn’t leave much behind. Not property or money. A nice car and a bunch of hoarded boxes.

After finishing the fire season, I found a therapist and started working through some of my trauma, and the PTSD caused by her death. I registered for classes at the local community college just after I turned thirty.

The new chapter

Two years after that, I started as an undergrad at Syracuse University, a school I admired. Being an older undergraduate was difficult. My weekly spending budget for my first year of school was $45, I couldn’t even afford a winter jacket. I couldn’t afford snow boots. I felt isolated because of my age and economic status. My studies overwhelmed me, but I refused to get anything less than an A in any class.

The years after my mother’s death were very dark, lonely and isolated, but slowly things began to get better. I started making some friends in town and worked as a literacy tutor in underserved schools. Then I got a merit scholarship. I was allowed to take a graduate class with Dana Spiotta, who taught in the graduate creative writing program.

I applied for the prestigious program and, the spring of my last year, was accepted. It’s a fully funded program, so I was given a stipend. I began to embrace my differences and to understand that my unique perspective was valuable.

Throughout the graduate program I worked on a novel, a fictionalized story of my mom’s suicide and my life as a firefighter, but despite getting a lot of great feedback no one would represent me. Upon graduation, I traveled to Southeast Asia, something I’d been wanting to do for nearly two decades. While I was there, I had a memoir piece published online, and an agent contacted me, wanting to represent me.

When I came back to Seattle and took a full-time nanny job, I wrote a book proposal, working in the early morning hours and on weekends, and then sold my book in the spring of 2019.

Selling a book didn’t solve all of my problems. I still struggle financially. I am still trying to find my place as a writer. My book doesn’t yet have a publication date. But I am better. I no longer need to be a firefighter to feel secure. However precarious it may feel, I am a writer. And I’m grateful for that.

Stacy Selby (they/them) is a writer currently working on a book about wildland firefighting and ecology. They also have a newsletter called FIRES. Stacy lives in Seattle with their cat, Leeloo.